Periorbital Eczema in Sheep:

When Pink Eyes Signal a Feeding Problem

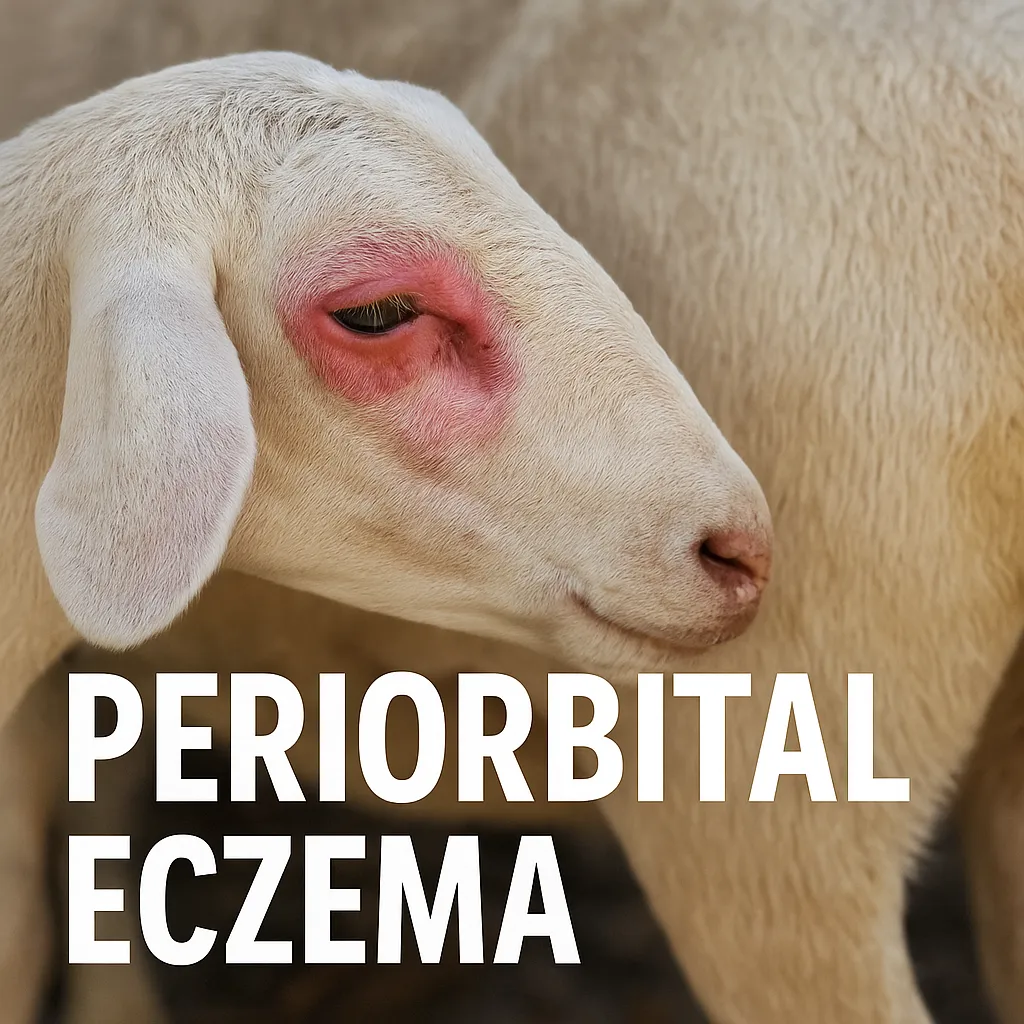

Two sheep in the flock looked out of place. Both had swollen, angry pink skin surrounding their eyes—the kind of inflammation that makes you wince just looking at it. The tissue appeared raw in places, puffy in others, and the sheep were clearly struggling with impaired vision. But here's what seemed odd: no discharge. No crusty buildup, no tears streaming down their faces, none of the telltale signs of pink eye that every shepherd learns to recognize.

Treatment began immediately—LA 200 for systemic bacterial control, topical tetracycline ointment applied directly to the inflamed skin, and careful monitoring over the following days. The intervention worked. The swelling decreased, the sheep's vision improved, they returned to normal feeding behavior. Success, right?

Except for one thing: the pink remained.

That persistent pink discoloration, visible weeks after successful treatment, holds the key to understanding periorbital eczema—a condition that's become increasingly common in modern sheep operations and often misunderstood even by experienced shepherds.

What Is Periorbital Eczema?

Periorbital eczema is a bacterial skin infection surrounding the eyes caused by Staphylococcus aureus. Unlike infectious keratoconjunctivitis (pink eye), which attacks the eye itself and produces discharge, periorbital eczema remains strictly a skin condition. The bacteria invade traumatized skin around the eyes, triggering intense inflammation that creates those characteristic swollen, pink-rimmed eyes.

The condition follows a predictable pattern: skin trauma creates entry points for bacteria, Staph aureus colonizes the damaged tissue, inflammatory response causes dramatic swelling and pink discoloration, and vision becomes impaired or blocked entirely. But here's the crucial detail that catches many producers off guard—even after the infection clears, that pink discoloration can persist for weeks or months.

This lingering pink isn't treatment failure. It's the normal healing trajectory of inflamed periorbital tissue. The veterinary literature consistently describes "sharply demarcated hair loss extending two to three centimeters around the eyes" as the signature mark of healed periorbital eczema. That pink you're seeing? It's damaged tissue slowly regenerating, hair follicles gradually recovering, and normal pigmentation working its way back.

The Feeding Trough Connection

Periorbital eczema isn't contagious. You won't see it spread from sheep to sheep like wildfire through your flock. Instead, this condition emerges from a management issue that's hiding in plain sight: inadequate feeding space.

Picture feeding time at a crowded trough. Sheep jostle for position, pushing and shoving, their heads rubbing against metal edges and wooden sides. Every competitive meal creates micro-abrasions around the eyes and face—tiny scratches and scrapes that are invisible at first but perfect entry points for Staphylococcus aureus lurking in the farm environment.

The bacteria don't need much of an invitation. Once they breach the skin's protective barrier through these feeding-related injuries, they multiply rapidly. What started as "we need a bigger trough" becomes "we need antibiotics and individual animal care."

Research and field experience have established clear guidelines: sheep need 45 centimeters (approximately 18 inches) of linear trough space per animal. For ring feeders, provide at least 15 centimeters per head. When those standards aren't met, periorbital eczema emerges as the visible symptom of invisible crowding stress.

Recognizing the Condition: What to Look For

Periorbital eczema presents with distinctive characteristics that separate it from other eye conditions:

Primary Clinical Signs:

Severely swollen eyelids—often puffy enough to completely obstruct vision

Pink to reddish inflamed skin encircling the eyes

Raw-looking patches where hair has been rubbed or damaged

Bilateral presentation common (both eyes affected)

Critically: No discharge from the eyes themselves

Secondary Effects:

Vision impairment ranging from mild to complete blindness

Disorientation, bumping into fences or feeders

Difficulty locating food and water

Rapid weight loss in affected animals

Increased vulnerability to injury from environmental hazards

That absence of discharge is your diagnostic key. Eye discharge—whether watery, mucoid, or purulent—points toward infectious keratoconjunctivitis or other ocular infections. Periorbital eczema keeps its drama on the skin's surface, where you can see inflammation and swelling but won't find fluid weeping from the eyes.

Why This Matters More Than You Think

Periorbital eczema strikes hardest during late pregnancy, when ewes can least afford vision problems. A sheep that can't see properly struggles to find adequate nutrition. That nutritional deficit cascades into pregnancy toxemia (twin lamb disease), reduced body condition scores, and ultimately compromised milk production after lambing. For ewes carrying multiples, temporary blindness can mean the difference between successful lambing and metabolic disaster.

Even in non-pregnant stock, vision impairment affects every aspect of welfare and productivity. Blind sheep fall into ditches, become entangled in fencing, fail to reach water sources during hot weather, and simply can't compete for feed in group settings. The economic arithmetic adds up quickly: veterinary costs, labor for individual animal care, production losses from reduced weight gain, occasional mortality from misadventure or secondary complications.

Differential Diagnosis: What Else Could It Be?

Several conditions can affect the area around sheep eyes. Accurate diagnosis matters because treatment strategies differ:

Infectious Keratoconjunctivitis (Pink Eye):

Caused by Chlamydia psittaci or Mycoplasma conjunctivae

Key difference: Produces tear-staining and mucopurulent discharge down the face

Affects the cornea directly, causing opacity and cloudiness

Often associated with harsh weather—high winds, driving snow, dust storms

Highly contagious, spreads rapidly through close contact at troughs

Orf/Soremouth with Facial Extension:

Viral disease caused by parapoxvirus

Key difference: Primary lesions are crusty, proliferative scabs on lips and muzzle

Can extend to periorbital areas in severe cases

Sometimes complicated by secondary Staph aureus infection

More common in young lambs, highly contagious

Entropion (Inverted Eyelid):

Hereditary condition, present at birth or shortly after

Key difference: Eyelashes rub directly on cornea

Causes obvious pain and frequent blinking

Produces purulent discharge from corneal irritation

Usually bilateral, affects young lambs

Photosensitization:

Reaction to certain plants or liver dysfunction

Key difference: Affects all non-pigmented, sun-exposed areas

Ears particularly vulnerable and may become necrotic with "curled-up" appearance

Animals actively seek shade and show head-shaking behavior

Often associated with swelling of face and lower limbs

Listeriosis (Silage Eye):

Associated with big bale silage feeding

Key difference: Causes bluish-white corneal opacity within days

Produces excessive tearing and forced eyelid closure

Photophobia (light sensitivity) prominent

Can affect sheep of any age

When examining affected animals, focus on lesion distribution and presence or absence of discharge. Periorbital eczema's signature presentation—swollen, pink, raw skin around eyes without ocular discharge—combined with inadequate trough space discovered during farm investigation, clinches the diagnosis.

Treatment: What Works and What to Expect

Here's the good news: periorbital eczema responds remarkably well to appropriate treatment. But "responds well" needs clarification, because functional improvement and cosmetic recovery operate on very different timelines.

Effective Treatment Protocol:

Systemic Antibiotics: Long-acting oxytetracycline (LA 200) at appropriate dosing provides sustained antibiotic coverage. Alternative options include procaine penicillin, though shorter duration of action may require repeat administration. The systemic approach fights infection from within, reaching bacteria colonizing the inflamed tissue.

Topical Application: Tetracycline ophthalmic ointment applied directly to affected skin delivers medication right where it's needed. Some producers also use topical antibiotic sprays or ointments labeled for wound care. The topical component provides direct bacterial control and may offer some pain relief to inflamed tissue.

Supportive Care:

House severely affected animals separately, especially those with bilateral vision impairment

Ensure easy access to feed and water—place buckets and hay where blind sheep can find them without searching

Monitor daily for signs of improvement and ability to eat/drink adequately

Protect vision-impaired sheep from environmental hazards during recovery

The Real-World Timeline:

In the case of those two affected sheep mentioned earlier, treatment with LA 200 and topical tetracycline produced clear functional improvement. The swelling decreased, vision returned, normal behavior resumed. Treatment worked—the infection was controlled. But that pink discoloration around their eyes? Still visible weeks later.

This is normal. This is expected. This is not treatment failure.

Here's what the recovery timeline actually looks like:

24-48 hours: Noticeable reduction in swelling, improved vision, sheep returning to normal feeding patterns

3-7 days: Significant improvement in comfort level, reduced inflammation, functional recovery essentially complete

2-4 weeks: Gradual fading of pink discoloration, tissue remodeling continues

4-8 weeks: Hair begins regrowing in affected areas where follicles were damaged

2-6 months: Complete restoration of normal appearance, pigmentation fully returns

The bacterial infection clears quickly—that happens in days with proper antibiotic therapy. But the tissue damage and inflammatory response take far longer to fully resolve. That persistent pink represents healing tissue, not ongoing infection.

The practical implication? Judge treatment success by functional criteria: Is the swelling decreasing? Can the sheep see better? Are they eating and drinking normally? Are they navigating their environment without difficulty? If the answers are yes, treatment is working—even if those eyes still look pink.

Prevention: Rethinking Infrastructure

Treating periorbital eczema addresses the symptom. Preventing it requires addressing the cause. And the cause, more often than not, lives at your feeding stations.

Space Requirements That Actually Work:

The research-backed standard is 45 centimeters (roughly 18 inches) per sheep at linear troughs. This isn't arbitrary—it's the spacing that allows animals to eat comfortably without aggressive competition. For ring feeders, provide at least 15 centimeters per head. Yes, this might mean purchasing additional or larger troughs. But compare that one-time infrastructure investment to recurring costs of treating periorbital eczema, lost production from affected animals, and labor for individual care.

Effective Feeding Station Options:

The right feeding system can eliminate periorbital eczema from your operation entirely. Here are proven solutions that provide adequate space and reduce injury risk:

Linear Trough Systems: Traditional linear troughs work well when properly sized. For a flock of 20 sheep, you need 9 meters (nearly 30 feet) of trough space to meet the 45-centimeter-per-head standard. Sounds like a lot? That's because it is—and that's the point. Options include:

Commercial galvanized steel troughs with rolled edges (no sharp seams)

Plastic feed bunks designed for sheep—lightweight, smooth surfaces, easy to clean

Wooden troughs lined with smooth material—affordable DIY option, ensure no splinters or rough edges

Rubber or plastic feed pans arranged in a line—flexible, can be repositioned as needed

Look for designs with:

Rolled or rounded edges rather than sharp 90-degree corners

Appropriate height (roughly 40-50cm for adult sheep)

Stable bases that won't tip during competitive feeding

Easy-to-clean surfaces that don't harbor bacteria

Circular/Ring Feeders: Ring feeders concentrate animals but require careful sizing. For ring feeders, calculate based on circumference—remember, you need 15 centimeters per sheep minimum. A 20-sheep group needs a feeder with at least 3 meters of circumference (roughly 1 meter diameter). Better designs include:

Hay ring feeders with grain pan attachments—allows simultaneous hay and concentrate feeding

Tombstone-style barriers—sheep insert heads through openings, reducing competition

Adjustable height ring feeders—can modify as lambs grow

Covered ring feeders—protect feed from weather, reduce waste

Creep Feeders for Lambs: Young lambs face the highest risk since they're most vulnerable to being pushed around by adults. Creep feeding systems that exclude ewes give lambs competitive-free eating space:

Adjustable panel creep gates—adults can't access lamb feeding area

Low-clearance creep feeders—lambs pass under, ewes cannot

Multiple small feeding stations rather than one large one—spreads lambs out naturally

Snacker/Paddle Feeders: These mechanical systems revolutionize feeding management by eliminating troughs entirely. A rotating paddle or conveyor distributes concentrate feed directly onto clean pasture in a line or arc pattern. Benefits include:

Zero head-to-head competition—sheep spread out naturally along the feed line

No trough injuries possible—nothing to bump against or scrape on

Mimics natural grazing behavior—heads down, spread out

Reduces aggression and stress during feeding time

Self-cleaning system—no bacterial buildup in equipment

While more expensive upfront (typically $2,000-$5,000 depending on size and features), snacker systems pay for themselves through reduced veterinary costs, better animal welfare, and improved feed efficiency. Particularly valuable for operations with chronic periorbital eczema problems.

Feed Bunk Systems: Popular in commercial operations, feed bunk designs with individual stanchions or barriers give each animal defined space:

Locking stanchion systems—each sheep has an assigned spot, locked in during feeding

Divider panels at regular intervals—creates individual feeding zones without locks

Slant-bar designs—angled bars allow head insertion but limit sideways movement

These systems work exceptionally well for pregnant ewes or show animals where you're monitoring individual intake carefully.

Ground Feeding: The simplest solution for small flocks: scatter concentrate feed on clean pasture. This eliminates equipment entirely and provides unlimited "trough space." Considerations:

Works best with pelletized feeds that don't blow away

Requires clean, dry ground—not practical in muddy conditions

Feed in different location each time to prevent bare spots

May result in some feed waste but eliminates competition injuries entirely

Best combined with good pasture management

Multiple Station Strategy: Instead of one large feeding area, consider multiple smaller stations spread throughout your pen or pasture:

Creates sub-groups that self-sort by dominance

Timid animals can access feed at less crowded stations

Reduces traffic jams and pushing at any single location

Provides backup options if one station becomes inaccessible

For example, a flock of 30 sheep might benefit more from three 10-sheep capacity troughs positioned in different areas than one 30-sheep capacity central trough.

Design Details Matter:

Beyond the feeding system itself, implementation details make the difference:

Smooth edges everywhere—no sharp corners or rough welds that scrape skin

Appropriate heights—roughly 40-50cm for adult sheep, lower for lambs

Adequate lighting—animals see each other, avoid collisions, reduce stress

Secure mounting—troughs that shift or tip create hazard zones

Regular maintenance—inspect monthly for damage, sharp edges, rough spots

Strategic placement—avoid corners or dead-ends where timid sheep get trapped

Weather protection—covered feeding areas reduce competition during rain/snow

Stocking Density:

Sometimes the problem isn't trough size—it's total animal numbers. High-density operations without proportionally scaled infrastructure create the perfect storm for periorbital eczema. Evaluate whether you need larger facilities or fewer animals per housing area.

Environmental Management:

Keep housing well-ventilated to reduce stress and disease pressure

Provide adequate shelter from harsh weather

Maintain clean, dry conditions that don't promote bacterial growth

Consider separating aggressive eaters or establishing feeding groups by size and competitiveness

When to Call the Veterinarian

While periorbital eczema typically responds to standard antibiotic treatment, certain situations demand professional veterinary attention:

Immediate Veterinary Consultation Needed:

First occurrence in your flock (establish accurate diagnosis and baseline treatment protocol)

Multiple animals affected simultaneously (suggests broader management issues requiring systematic solutions)

Pregnant ewes affected within four weeks of lambing (risk of pregnancy toxemia complications)

No improvement within 48-72 hours of appropriate antibiotic treatment

Signs of other conditions developing—discharge appearing, corneal cloudiness, systemic illness

Uncertainty about diagnosis—several conditions can look similar, especially in early stages

A veterinarian can confirm periorbital eczema versus other conditions, rule out concurrent diseases, provide guidance on antibiotic selection and dosing for your specific situation, and help you identify and correct the underlying management factors driving the condition.

The Management Lesson

Periorbital eczema functions as a management report card. When multiple sheep develop this condition, your flock is communicating something important about infrastructure and husbandry practices. Rather than viewing it purely as a bacterial infection requiring antibiotic treatment, recognize it as valuable feedback about feeding space, competition, and potentially stocking density.

The condition rarely occurs in extensively managed sheep with ample grazing and minimal supplemental feeding competition. It's primarily a problem of intensification without proportional infrastructure adjustment. As operations increase stocking densities to improve economic efficiency, details like trough length and feeder design must scale accordingly—not as afterthoughts, but as critical components of animal welfare and productivity.

Living with the Pink

Understanding that pink discoloration persists long after successful treatment changes how you evaluate recovery and make management decisions. Those two sheep that responded well to LA 200 and topical tetracycline but retained pink around their eyes? They're fine. The infection cleared, vision returned, function restored. The pink is simply the visible timeline of tissue recovery—a process measured in months, not days.

This knowledge matters for several reasons:

Treatment Decisions: Don't retreat animals repeatedly just because pink remains visible. Functional improvement indicates success; cosmetic restoration follows on its own schedule.

Record Keeping: Note affected animals and document their recovery timeline. This creates valuable baseline data for evaluating future cases and assessing whether prevention strategies are working.

Culling Decisions: Don't cull animals solely based on residual pink discoloration or hair loss around eyes. These cosmetic effects fade completely with time and don't impact long-term productivity.

Prevention Monitoring: Track new cases over time. If feeding infrastructure improvements are effective, you should see decreasing incidence of periorbital eczema in subsequent feeding periods.

The Path Forward

Periorbital eczema might seem like a straightforward condition—antibiotics resolve it, after all. But its presence signals an opportunity for meaningful improvement in your operation. Those swollen, pink-rimmed eyes are asking you to evaluate feeding infrastructure, competition dynamics, and whether intensification has outpaced facilities.

The solution combines immediate treatment with long-term prevention. Treat affected animals appropriately and expect functional improvement within days, even though cosmetic recovery takes months. Simultaneously, audit your feeding setup and make necessary changes: longer troughs, additional feeding stations, alternative feeding systems, or adjusted stocking density depending on your specific situation.

Your sheep will tell you when you've succeeded. Feeding time transforms from competitive chaos to calm eating. New cases of periorbital eczema disappear from your records. Veterinary bills for this particular condition vanish from your budget. Those are the metrics that matter—not how quickly pink fades from treated animals' eyes, but whether new cases stop appearing in the first place.

The pink reminds us that healing takes time, that visible recovery lags behind functional recovery, and that successful treatment means restoration of health and comfort, not immediate restoration of appearance. It's a lesson worth remembering across all aspects of animal care.

Have you dealt with periorbital eczema in your flock? How long did the pink discoloration persist after treatment in your experience? What feeding management changes proved most effective for prevention? Share your observations in the comments below.